Simplifying JavaScript Prototypes in Constructor Invocation with Simple Words and Diagrams

Summarize with AI:

Learn about JavaScript prototypes and prototype chains, which helps explain how objects are created.

As a JavaScript developer, you have likely heard the sentence, “In JavaScript, every object is created from an existing object.”

But since there are multiple ways (four, to be precise) to create an object—for example, using a function constructor or a class—that statement can seem false. How can an object be created from an existing object?

In this article, my goal is to give you a clear understanding of JavaScript prototypes and how objects are created. By the end, you’ll be able to grasp these concepts with the help of a diagram like the one shown below:

Let’s start with the following statement:

“In JavaScript, every object is linked to an existing object, and that existing object is known as the prototype of that object.”

So, otherwise stated, every JavaScript object you create is linked to its prototype object. That means a new JavaScript object is always linked to its prototype object.

Consider this constructor function:

function Product(name, price) {

this.name = name;

this.price = price;

}

let p1 = new Product('Pen', 1.2);

console.log(Object.getPrototypeOf(p1));

When you create p1 with new Product(...), JavaScript does two important things for you:

- It creates a new object

p1. - It sets the internal prototype of that new (

p1) object ([[Prototype]]) toProduct.prototype.

So p1 is linked to the Product.prototype object.

Any other object created using the new Product(...) will be linked to the same Product.prototype object.

let p2 = new Product('Pencil', 0.8);

console.log(Object.getPrototypeOf(p2));

Since both p1 and p2 are created using the same constructor function Product, they are linked to the same prototype object and have read access to the properties of the prototype object.

Before moving forward, let’s look at the different ways to create an object in JavaScript:

- Using a function as a constructor

- Using an object literal

- Using a class

- Using the

Object.create()method

Constructor Invocation Pattern

First, let’s start with the function as a constructor. When you use a function to create an object, it is also known as the Constructor Invocation Pattern.

In JavaScript, every regular function (but not arrow functions) has a prototype object. When you use a regular function as a constructor, the newly created object’s internal prototype ([[Prototype]]) is linked to that function’s prototype. Arrow functions don’t have a prototype property, so they can’t be used as constructors. To demonstrate this, print the following two values:

function Product(title, price) {

this.title = title;

this.price = price;

}

console.log(Product.prototype); // {}

var Invoice = (title, price) => {

this.title = title;

this.price = price;

}

console.log(Invoice.prototype); // undefined

As the output shows, an arrow function’s prototype is undefined, so it can’t be used as a constructor to create objects.

So, we cannot use an arrow function as a constructor to create an object.

Prototype Diagram

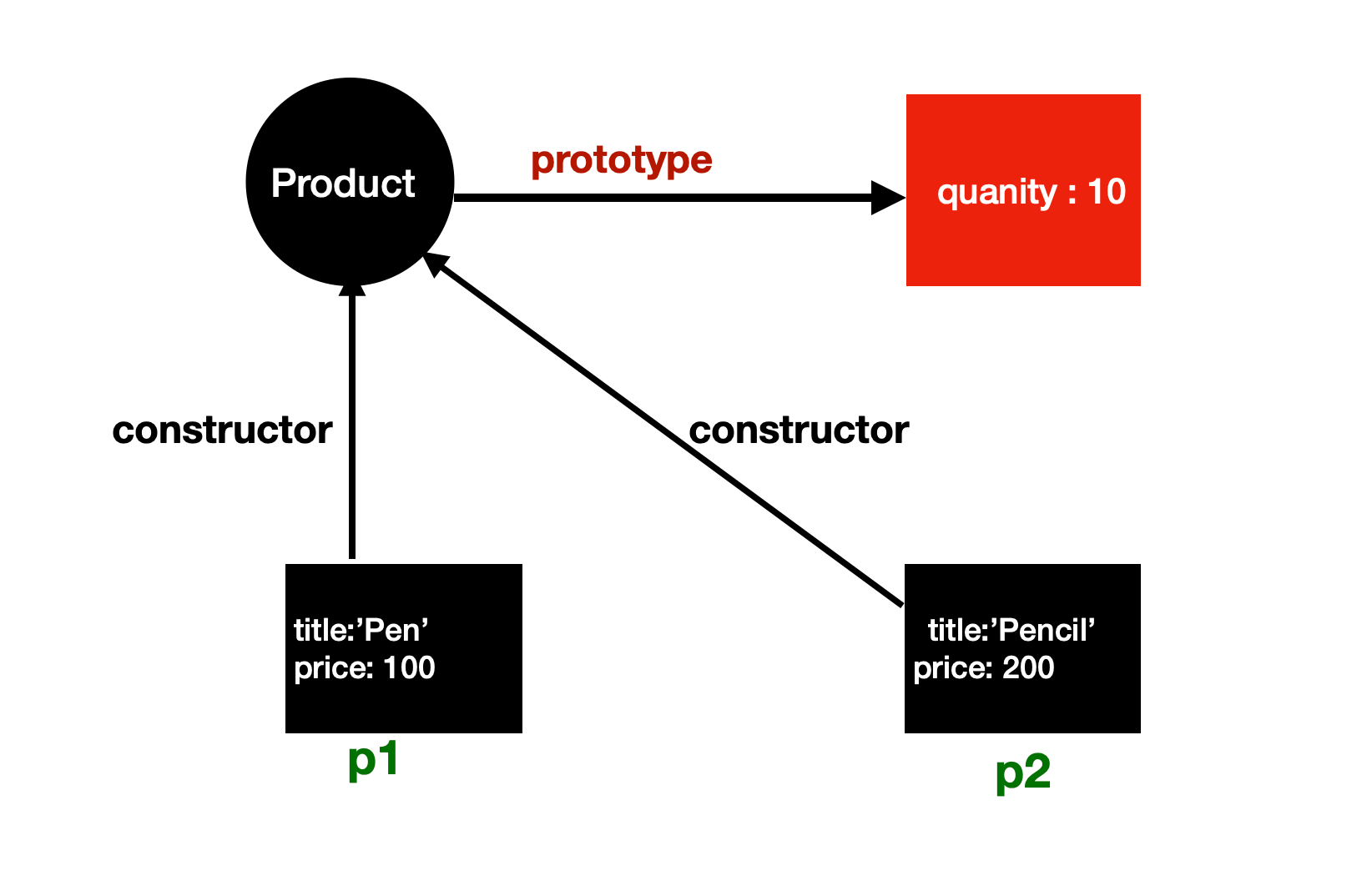

In this section, let’s build a prototype diagram step-by-step using the Constructor Invocation Pattern to create objects. Some rules we are going to follow are as follows:

- Draw a function as a circle

- Draw the object as a rectangle

- Draw a prototype object as a red rectangle

We have a Product function:

function Product(title, price) {

this.title = title;

this.price = price;

}

Let us draw the Product function as a circle:

Next, add a quantity property to Product function:

Product.prototype.quantity = 10;

This is represented in the diagram using red reactance and an arrow from Product function below:

Next, let’s create two objects, p1 and p2, from the Product constructor as shown below:

let p1 = new Product('Pen', 100);

let p2 = new Product('Pencil', 200);

This can be depicted in the diagram as below:

Because p1 and p2 are objects, we draw them as rectangles. And since the Product constructor created both, each rectangle has an arrow pointing to the Product function. If you log p1.constructor or p2.constructor, it returns Product.

console.log(p1.constructor === Product);// true

console.log(p2.constructor === Product); // true

So far, we have connected the instances, the constructor and the prototype.

console.log(p1.quantity); // 10

console.log(p2.quantity); // 10

console.log(p1.hasOwnProperty('quantity'));// false

console.log(p2.hasOwnProperty('quantity')); // false

Now, when you read the quantity property on p1 or p2, JavaScript follows these steps:

- Check the object itself (

p1) for its own property named quantity. If found, return that value and stop. - If not found, follow the internal

[[Prototype]]link toProduct.prototypeand look for quantity there. If found on the prototype, return that value and stop. - If still not found, continue up the prototype chain to

Object.prototypeand check there. - If the property is nowhere on the chain, return undefined.

Now you can follow the prototype chain to read the quantity value for p1 and p2. In fact, by looking at the diagram, you can see that p1.quantity resolves to the same value as p1.constructor.prototype.quantity, provided p1 does not have its own quantity property.

console.log(p1.quantity == p1.constructor.prototype.quantity); // true

console.log(p2.quantity == p2.constructor.prototype.quantity); // true

console.log(p1.quantity)// 10

console.log(p2.quantity)// 10

console.log(p1.constructor.prototype.quantity); // 10

console.log(p2.constructor.prototype.quantity); // 10

The prototype is reachable in two ways:

- Through the constructor (

obj.constructor.prototype) - Directly via the instance’s internal

[[Prototype]]

When you create an object with a constructor, JavaScript sets the instance’s [[Prototype]] to that constructor’s prototype. Most JavaScript engines expose that link as obj.__proto__. So let’s modify the prototype diagram to depict this.

As you can see, p1.__proto__ refers to the same object as p1.constructor.prototype, and the __proto__ of p1 is identical to the __proto__ of p2. Hence, JavaScript returns true for the comparisons below.

console.log(p1.quantity == p1.__proto__.quantity); // true

console.log(p2.quantity == p2.__proto__.quantity); // true

console.log(p1.constructor.prototype.quantity == p1.__proto__.quantity); // true

console.log(p2.constructor.prototype.quantity == p2.__proto__.quantity); // true

console.log(p1.__proto__ == p2.__proto__); // true

To summarize, when you read a property of an object:

- JavaScript reads the property in the object itself.

- If JavaScript finds the property, it reads the value.

- If JavaScript does not find the property, it traverses to the object’s prototype.

- If JavaScript finds the property, it reads the value.

- If JavaScript cannot find the property, it traverses up to the

Object.prototype. - If it does not find a property, it reads it as undefined.

The prototype diagram also shows that there are multiple paths to reach an object’s prototype. For instance, both p1.constructor.prototype and p1.__proto__ lead to the same prototype object of p1.

Bringing it all together, we now have a constructor function and two objects created from it, as shown below:

function Product(title, price) {

this.title = title;

this.price = price;

}

Product.prototype.quantity = 10;

let p1 = new Product('Pen', 100);

let p2 = new Product('Pencil', 200);

The above code can be translated to a prototype diagram as shown below.

Now you can easily reason through the following question by referring to the prototype diagram:

console.log(p1.constructor === Product);// true

console.log(p2.constructor === Product); // true

console.log(p1.quantity); // 10

console.log(p2.quantity); // 10

console.log(p1.hasOwnProperty('quantity'));// false

console.log(p2.hasOwnProperty('quantity')); // false

console.log(p1.quantity == p1.constructor.prototype.quantity); // true

console.log(p2.quantity == p2.constructor.prototype.quantity); // true

console.log(p1.quantity)// 10

console.log(p2.quantity)// 10

console.log(p1.constructor.prototype.quantity); // 10

console.log(p2.constructor.prototype.quantity); // 10

console.log(p1.quantity == p1.__proto__.quantity); // true

console.log(p2.quantity == p2.__proto__.quantity); // true

console.log(p1.constructor.prototype.quantity == p1.__proto__.quantity); // true

console.log(p2.constructor.prototype.quantity == p2.__proto__.quantity); // true

console.log(p1.__proto__ == p2.__proto__); // true

Write Operation

By default, JavaScript lets you add properties to an object dynamically. For example, the following operation works perfectly fine:

var Foo = {};

Foo.koo = 9;

In JavaScript, write operations always target the object itself rather than its prototype chain. This means that when you assign a new property—for example, p1.color = "red"—the property is created as its own property on p1.

Other instances created from the same constructor, such as p2, will not inherit this property because it exists only on p1 and not on the shared prototype.

let p1 = new Product('Pen', 100);

p1.color = "red";

let p2 = new Product('Pencil', 200);

console.log(p1.color); // red

console.log(p2.color); // undefined

For the p2 object, the color value is undefined because no object in its prototype chain defines a color property.

In JavaScript, if an object defines a property with the same name as one that exists on its prototype, the object’s own property takes precedence. This behavior is known as property shadowing. When property shadowing occurs, lookups on the object will return the value of the own property, effectively hiding the corresponding property on the prototype without modifying it.

Product.prototype.quantity = 10;

let p1 = new Product('Pen', 100);

p1.color = "red";

let p2 = new Product('Pencil', 200);

p2.quantity = 56;

console.log(p1.color); // red

console.log(p2.color); // undefined

console.log(p1.quantity); // 10

console.log(p2.quantity); // 56

Now p2 has its own quantity property, so when you access p2.quantity, JavaScript reads it directly from the p2 object instead of the prototype. The updated prototype diagram illustrates this as shown below:

This in Prototype

Let’s now look at how this behaves in the prototype chain. We’ll modify the base code as shown below:

function Product(title, price) {

this.title = title;

this.price = price;

}

Product.prototype.quantity = 10;

Product.prototype.log = function(){

console.log(`${this.title} costs ${this.price} and quantity available : ${this.quantity}`);

}

We’ve added a function named log to the Product prototype, and, inside it, we use the this keyword to access the object’s properties. The log method is added to the prototype, so all Product instances can call this method to display their information.

let p1 = new Product('Pen', 100);

let p2 = new Product('Pencil', 200);

p1.log();

p2.log();

When the log method is called on p1, the value of this inside the method refers to the p1 object. Similarly, when called on p2, this refers to the p2 object.

If you want to set a different object as the value of this, you can use the Indirect Invocation Pattern with methods like call, as shown below.

p1.log.call(p2);

The value of this is not determined by where a function is defined, but by how it is called.

p1.log()→ Insidelog,thisrefers to p1.p2.log()→ Insidelog,thisrefers to p2.

That’s why the same method on the prototype works for both objects—this always points to the calling object.

Summary

- In JavaScript, every object has an internal link to another object called its prototype. This link forms a chain, known as the prototype chain, which is used for property and method lookup.

- As an arrow function does not have a prototype object, it cannot be used as a constructor.

- If you assign a property directly to an instance, it shadows the prototype property.

- The write operation (

=) always creates or updates its own properties on the object, not on the prototype. - When you read a property, JavaScript looks for the property on the object itself. If not found, move to the object’s prototype and continue up the chain until

Object.prototype. If still not found, returnundefined. - Using the Indirect Invocation Pattern, you can explicitly pass the value of this object to the method created on the prototype object.

All of the above learning can be summarized in the following prototype chain diagram.

Dhananjay Kumar

Dhananjay Kumar is the founder of nomadcoder, an AI-driven developer community and training platform in India. Through nomadcoder, he organizes leading tech conferences such as ng-India and AI-India. He partners with startups to rapidly build MVPs and ship production-ready applications. His expertise spans Angular, modern web architecture and AI agents, and he is available for training, consulting or product acceleration from Angular to API to agents.