React Basics: Thinking in React

Summarize with AI:

To be an effective React developer, you need to learn how to think in React, to structure your app UI component hierarchy so that the state flows in one direction.

When you’re new to React, it’s easy to focus on JSX, hooks, props and state. But what really unlocks the power of React isn’t memorizing APIs. It’s learning how to think in React.

Once you understand React’s mental model, UI development stops feeling like a tangle of jQuery patches or DOM manipulations and instead feels like snapping together Lego pieces.

This guide walks you through how to think in React, step by step, so you can build interfaces that are clean, scalable and easy to reason about.

Why ‘Thinking in React’ Is a Big Deal

If you’re coming from an HTML/CSS or jQuery background, you’re probably used to working with static templates and manually tweaking the DOM to make things interactive. React changes that completely.

In React, the UI is a direct reflection of your state. Instead of imperatively telling the DOM what to do, you simply describe how the UI should look based on the current state—and React takes care of keeping everything in sync. To make the most of this, you have to shift your mindset from “pages and DOM updates” to “components and state-driven UI.”

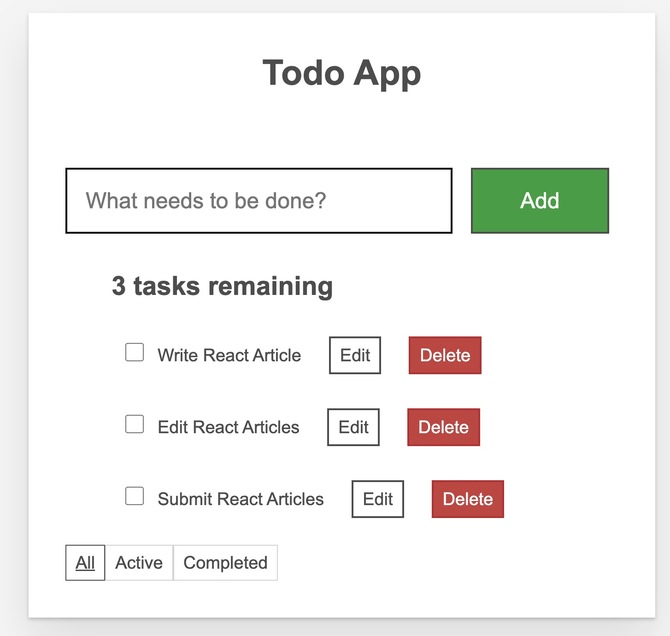

When building a user interface application, you’ll usually start with two things: a mockup from the designer and some data from the backend API. For this guide, we’ll use a simple todo app as our example.

Our todo application UI/Mockup will look like this:

And here’s the link to the source code: https://codesandbox.io/p/sandbox/todo-app-in-react-zqpth8.

And here’s the kind of JSON response we’d expect from an API (for now, we’ll hardcode it since we don’t have a real backend):

[

{ id: 0, title: "Write React Article", done: true },

{ id: 1, title: "Edit React Articles", done: false },

{ id: 2, title: "Submit React Articles", done: true },

]

According to the React documentation, to implement a UI in React, you typically follow five steps. We will utilize these techniques throughout the process of thinking through how to build the todo application.

Step 1: Break the UI into a Component Hierarchy

When you’re preparing to build a UI in React, the best starting point is a clear design. This may come from your product designer (using Figma, Sketch, Progress ThemeBuilder or similar), or you might create it yourself as a UX engineer. Either way, your primary task is to decompose that design into logical, reusable components.

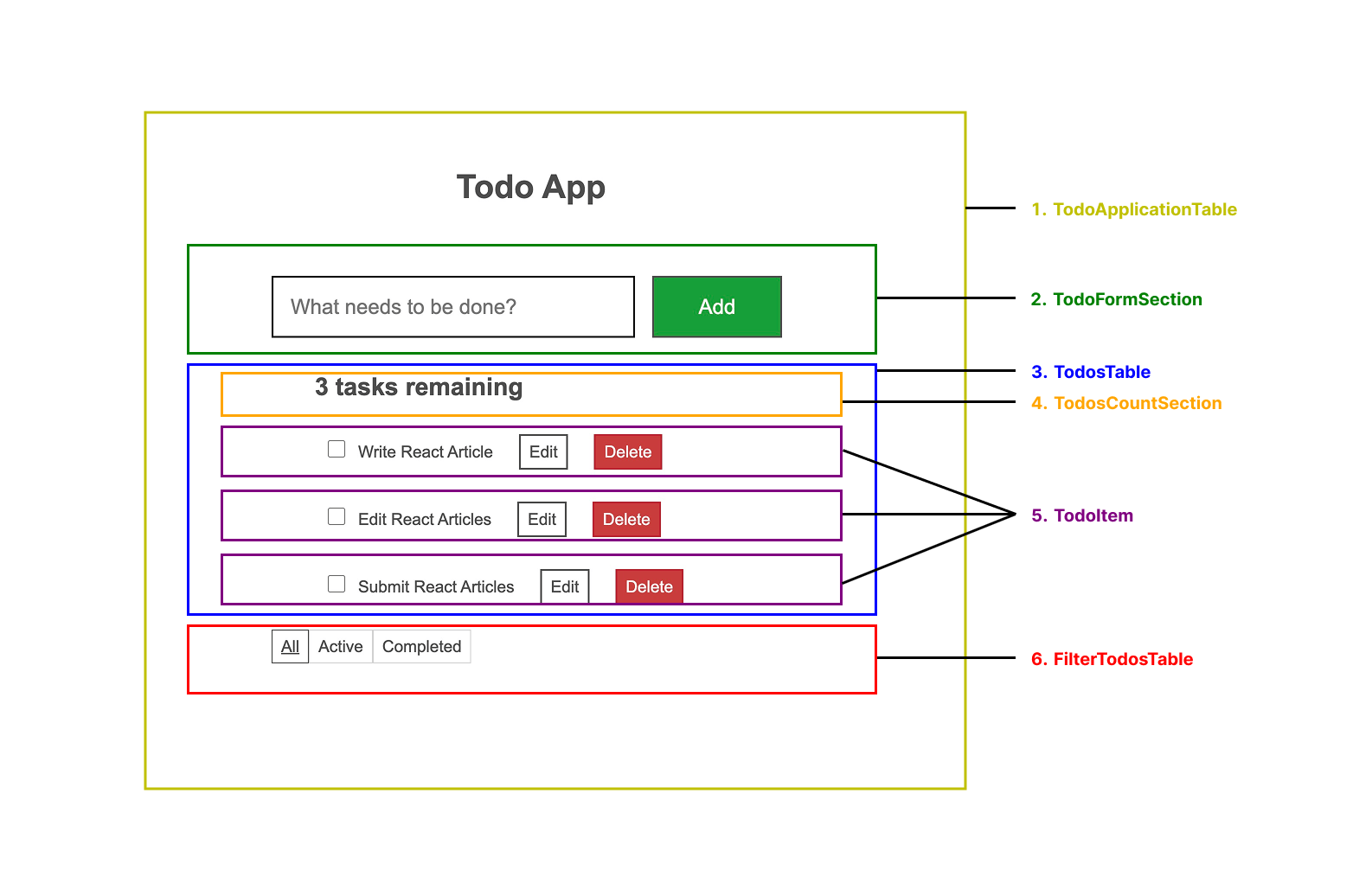

Let’s take our todo application as an example. The simplest way to begin is by outlining each component and subcomponent in the mockup and clearly labeling them. Many design tools streamline this by enabling designers to name layers or components directly in the file.

As you break down the design, keep these perspectives in mind:

- Programming perspective: Think in terms of the single responsibility principle. A component should ideally do one thing well. If it starts growing beyond that, break it into smaller subcomponents.

- CSS perspective: Imagine what you’d normally assign a class selector to. Components often map to those same chunks of UI, though not always as granular.

- Design perspective: Examine how layers are grouped and organized within the design file. That structure often hints at where components should be split.

In many cases, the structure of your backend data will also influence your component breakdown. Well-structured APIs often map neatly onto the UI—both follow the same information architecture. Break your UI into components so that each one corresponds to a specific part of your data model.

For our todo application, here’s a breakdown of six main components:

TodoApplicationTable(yellow): Wraps the entire app.TodoFormSection(green): Handles user input for adding todos.TodosTable(blue): Displays the list of todos along with related actions.TodosCountSection(orange): Shows the total number of todos.TodoItem(purple): Represents each individual todo and its actions.FilterTodosTable(red): Provides controls for filtering the todo list.

One thing to note: Inside TodosTable (blue), the TodoCountSection isn’t broken out as a separate component. That’s a design choice. It works fine to keep it in line for now, but if the header grows more complex later, you’ll likely want to extract it into its own TodosTableHeader component.

Once you’ve identified the pieces, the next step is to arrange them into a hierarchy. Components that appear inside others in the mockup should be children in your component tree. For our app, that looks like this:

TodoApplicationTable

├── TodoFormSection

└── TodosTable

├── TodoCountSection

├── TodoItem

└── FilterTodosTable

And that’s it for Step 1. You’ve successfully mapped your design into a clear component hierarchy.

Step 2: Build a Static Version in React

With your component hierarchy mapped out, the next step is to start coding. Before adding any interactivity, it’s best to build a static version of the UI—one that renders the correct structure and data but doesn’t handle any changes yet.

This step keeps things simple. Writing the static version is mostly about composition: putting components together and passing data down through props. Interactivity and state management come later, since those usually involve more thinking than typing.

At this stage, avoid using the state entirely. State is for dynamic, changing data. Since we’re only building the static skeleton, props are all you need. Parent components pass data to children, keeping your UI predictable and consistent.

You can approach this in two ways:

- Top-down: Start with higher-level components such as

TodoApplicationTableand work your way down. - Bottom-up: Start small with leaf components such as

FilterTodoTableand build upward.

For simple apps, top-down usually feels faster. For bigger projects, a bottom-up approach often helps keep things organized.

Here’s a static version of our todo application:

import "./styles.css";

const initialTodos = [

{ id: 0, title: "Write React Article", done: true },

{ id: 1, title: "Edit React Articles", done: false },

{ id: 2, title: "Submit React Articles", done: true },

];

function App() {

return (

<div className="todoapp stack-large">

<h1 className="header">Todo App</h1>

<TodoForm />

<TodoList todos={initialTodos} />

<FilterTodo />

</div>

);

}

export default App;

function TodoForm() {

return (

<form>

<input

type="text"

id="new-todo-input"

placeholder="What needs to be done?"

className="input input__lg"

name="text"

autoComplete="off"

/>

<button type="submit" className="btn btn__primary btn__lg">

Add

</button>

</form>

);

}

function TodoList({ todos }) {

return (

<>

<h2 id="list-heading">{todos.length} tasks remaining</h2>

<ul role="list" className="todo-list stack-large todo-exception">

{todos.map((todo) => (

<li key={todo.id} className="todo stack-small">

<div className="todo-cb">

<input id={`todo-${todo.id}`} type="checkbox" defaultChecked={todo.done} />

<label className="todo-label" htmlFor={`todo-${todo.id}`}>

{todo.title}

</label>

<button type="button" className="btn">

Edit <span className="visually-hidden">Edit</span>

</button>

<button type="button" className="btn btn__danger">

Delete <span className="visually-hidden">Delete</span>

</button>

</div>

</li>

))}

</ul>

</>

);

}

function FilterTodo() {

return (

<div className="filters btn-group todo-exception">

<button type="button" className="btn toggle-btn">

<span>All</span>

</button>

<button type="button" className="btn toggle-btn">

<span>Active</span>

</button>

<button type="button" className="btn toggle-btn">

<span>Completed</span>

</button>

</div>

);

}

At this point, each component is reusable and renders part of the data model. Notice how TodoList receives the list of todos as a prop and passes it down the tree. This is React’s one-way data flow in action: data always moves from parent to child, top to bottom.

No state yet—that comes in the next step when we make the app interactive.

Step 3: Identify the Minimal (but Complete) Representation of UI State

Now comes the key question: what actually changes in this UI?

To make your app interactive, you need to let users update the underlying data model. That’s where the state comes in. State is the minimal set of data your app needs to remember over time. The golden rule: keep your state DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself). Store only what’s essential and derive everything else from it when needed.

For example, in our todo app, you definitely need to store the list of todos as an array. But if you also want to display the total number of todos, you don’t keep that number in state—you just calculate it from todos.length.

Now, let’s apply this thinking to our todo application demo example. Here are the key pieces of data:

- The original list of todos

- The input text entered by the user

- The value of the checkbox

- The filtered list of todos

- The total number of todos

- The value of the todo currently being edited

Which of this should be state? To figure that out, apply three simple questions to each piece:

- Does it change over time? If no, it’s not state.

- Is it passed in from a parent via props? If yes, it’s not state.

- Can it be derived from existing state or props? If yes, it’s not state.

What’s left is probably state. Let’s go through them one by one again:

- The original list of todos → comes in via props, not state.

- The input text → changes over time, so yes, it’s state.

- Checkbox value → can be derived from the todos array, not state.

- Filtered list of todos → depends on user actions and changes over time, so yes, it’s state.

- The total number of todos → can be computed from

todos.length, not state. - The edited todo value → changes over time, so yes, it’s state.

That leaves us with three pieces of state. Everything else can (and should) be derived from these. Keeping your state minimal and explicit makes your app easier to reason about, debug and maintain.

Step 4: Identify Where Your State Should Live

Once you’ve identified the minimal pieces of state your app needs, the next step is figuring out which component should own that state. In React, data flows in one direction, from parent to child, so placing state in the right spot makes everything easier to manage.

If you’re new to this, it might feel a bit tricky, but you can work it out by following this process:

- For each piece of state, list all the components that depend on it.

- Find their closest common parent in the components tree.

- Decides the closest common parent in the component tree:

a. Most of the time, you’ll put it in that common parent.

b. Sometimes, it makes sense to lift the state even higher.

c. If no existing component feels right, create a new one just to hold the state and place it above the common parent.

This helps to manage the state at the right level, so data can flow down as props to all components that need it.

In the previous steps, you will have noticed we have three pieces of state in the todo application: the added todo text, the value of the edited todo and the filtered todo list. In this example, the state of todos is what’s common to every other component.

So, let’s go through our strategy for them:

- Identify components that use state:

TodosTableneeds to list todos based on the state of (added todo text, checkbox value, editing and filtering options).TodoFormSectionneeds to get the state of the title of the todo that’s been added.FilterTodosTableneeds to display the state of the filtering.

Find their common parent: The first component both components share is the

TodoApplicationTablewhich is the App component that housed all the components.Decide where the state lives: We’ll keep the states common state to all, which is the

todosstate and thefilteringstate, in the parent component. The new todo input state will be kept in theTodoFormSectioncomponent. In our code demo, we named the componentTodoForm.js.

Then add state to the component with the useState() hook. Hooks are a special function that enable you to “hook into” React. Add two state variables at the top of the App component which we can also refer to as TodoApplicationTable, and specify their initial state.

const [todos, setTodos] = useState(initialTodos);

const [filter, setFilter] = useState("All");

Remember, we’re using the initial mock data first. So we set the todos state to that data before adding any user-created items to the list. For filtering, the default state is set to All, which is why we’re using All as the initial value.

Then pass the todos as props to the TodoList components as a prop :

<TodoList todos={todos} />

For the next state to add todo from user input, open the TodoForm.js component, which can also be referred to as the TodoFormSection, and add one state variable at the top of the component:

const [title, setTitle] = useState("");

The next state is for editing the todo, also add one state variable at the top level of Todo components, which TodoList serves as a parent component too:

const [isEditing, setIsEditing] = useState(false);

At this point, you haven’t added any code to respond to user actions such as typing yet. This will be the final step.

Step 5: Add Inverse Data Flow

Now it’s time to wire up interactivity. At this point, our app renders correctly, and state flows down from parent to child. But React apps aren’t just about displaying data—they need to respond to user input. This is where inverse data flow comes in.

React makes this process explicit, which means a little more typing compared to traditional two-way data binding. If you try typing in the input or toggling the checkbox in the example, nothing happens. That’s intentional.

The goal is to update state whenever the user interacts with the form inputs. Since the todos state lives in the main parent component, only it can set the state of the todo. So for the TodoForm component to update the todos state whenever a user input a new todo, we need to pass the function that add the new todo to the lists of the todo to the TodoFrom components:

export default function TodoApp() {

const [todos, setTodos] = useState(initialTodos);

function handleAddTodo(title) {

setTodos([

...todos,

{

id: nextId++,

title: title,

done: false,

},

]);

}

…

return (

<div className="todoapp stack-large">

<h1 className="header">Todo App</h1>

<TodoForm onAddTodo={handleAddTodo} />

….

</div>

);

}

Then in your TodoForm add the the state and function to receive user input and call onAddTodo whenever user submits:

function TodoForm({ onAddTodo }) {

const [title, setTitle] = useState("");

const handleSubmit = (e) => {

e.preventDefault(); // prevent page refresh

if (!title.trim()) return; // optional: avoid empty todos

onAddTodo(title);

setTitle("");

};

return (

<form onSubmit={handleSubmit}>

<input

type="text"

id="new-todo-input"

placeholder="What needs to be done?"

className="input input__lg"

name="text"

autoComplete="off"

value={title}

onChange={(e) => setTitle(e.target.value)}

/>

<button type="submit" className="btn btn__primary btn__lg">

Add

</button>

</form>

);

}

We follow the same pattern for editing and toggling: App owns the state, defines an updater and passes it down.

export default function TodoApp() {

// …

function handleChangeTodo(nextTodo) {

setTodos(

todos.map((t) => {

if (t.id === nextTodo.id) {

return nextTodo;

} else {

return t;

}

})

);

function handleDeleteTodo(todoId) {

setTodos(todos.filter((t) => t.id !== todoId));

}

return (

<TodoList

todos={todos}

onChangeTodo={handleChangeTodo}

onDeleteTodo={handleDeleteTodo}

/>

);

}

Inside TodoItem, we call these functions when the user edits text, toggles a checkbox or deletes a task.

Repeat this process for the other components, adding inverse data flow with state and interactivity as needed. If you’re new to React, we’ll walk you through building this todo application from scratch in blog post React Basics: Interactivity and State.

Here’s the full code: https://codesandbox.io/p/sandbox/todo-app-in-react-zqpth8

Now the application is fully working:

Conclusion

“Thinking in React” is less about coding and more about adopting a new way of seeing UIs. You’re no longer shuffling DOM nodes by hand—you’re structuring your app as a hierarchy of components, each powered by state flowing in one direction. Once you grasp that, scaling your application feels far less intimidating because every piece has its place.

In this walk-through, we use a todo app to put React’s five-step process into practice: breaking down the UI, building a static version, identifying state, deciding where it belongs and implementing inverse data flow.

With this approach, you’re not just writing React, you’re thinking in React. And that mindset shift is what turns a beginner into a confident React developer.

David Adeneye Abiodun

David Adeneye is a software developer and a technical writer passionate about making the web accessible for everyone. When he is not writing code or creating technical content, he spends time researching about how to design and develop good software products.