Using the Zone of Proximal Development to Build Better Engineering Teams

Summarize with AI:

Through trial and error, I found that the best way to increase a new software engineer's productivity is by gradually increasing the difficulty and independence level at which they operate. Turns out the name for this is the zone of proximal development.

I’ve spent the past eight years leading software engineering teams at education technology companies, so I’ve had the opportunity to hire several early-career engineers. Through trial and error, I found that the best way to increase a new software engineer’s productivity is by gradually increasing the difficulty and independence level at which they operate.

I never had a name for this process until I hired a software engineer who was formerly a school principal. I started telling her about our onboarding process, and she stopped me and said, “I see, you’re using the zone of proximal development.”

What is the Zone of Proximal Development?

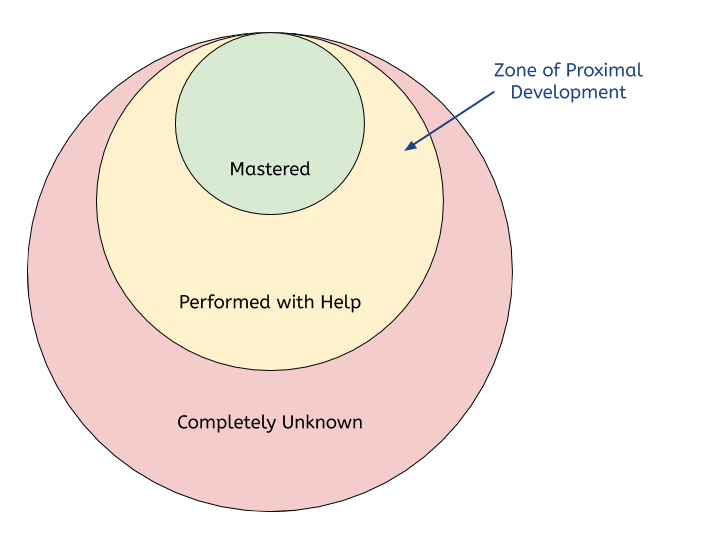

I had never heard the term before, but as I learned about the topic, I realized that it was a great mental model for teaching new skills. The zone of proximal development (abbreviated ZPD) describes the area of tasks that a learner can do only with a little bit of help.

Learning happens in this zone. Tasks that have already been mastered aren’t pushing the student enough, while tasks that are too advanced will be impossible for them to grasp. As a student learns, their zone of proximal development will change. Good teachers must create a framework for moving the bar a little bit higher every time that happens.

In education, this process is known as “scaffolding.” A teacher who is applying the zone of proximal development to their classroom will help each student stay in this zone by offering peer groups or hints to students who are struggling and raising the bar higher for students who have already crossed into mastery. This is incredibly hard to do with 30 kids having different skill levels, but it’s proven effective in numerous studies over the past few decades.

The ZPD in Engineering Education

The concept has been used in computer science and engineering education too. A 2013 paper by two Winona State University computer science professors concluded that using familiar and fun projects like game development is a better way to introduce students to the profession than purely conceptual knowledge:

We believe that optimal learning takes place for students when the material is within their cognitive capabilities, it is presented in a way that is familiar to them, and uses an application that is relevant or interesting to them … We need to both stay within the students’ developmental zone of proximal development as well as within their comfort zone.

– Learning Computer Science in the “Comfort Zone of Proximal Development”

Similarly, four Purdue engineering faculty members proposed using the zone of proximal development to increase innovative thinking in engineers. Their paper from the 2016 American Society for Engineering Education conference concludes:

For students to be innovative, they need scaffolding aligned with their current state of competencies. If projects that require or attempt to elicit innovation exist within what students can do unaided or outside what students can do with assistance, students’ interaction with innovation decreases.

– Innovation and the Zone of Proximal Development in Engineering Education

If you want new engineers to grow, you have to gradually push them beyond what’s comfortable and into the zone of proximal development.

Why Haven’t Employers Caught On?

While engineering education may be embracing the zone of proximal development and structured frameworks, I see little of it in engineering organizations today. Some companies refuse to hire junior engineers because they “don’t want their senior engineers to be "distracted" by having to teach them everything.

This sounds reasonable on the surface, but it’s extremely short-sighted. The #1 motivator cited by software engineers is “opportunities for professional growth,” so if you aren’t willing to train junior engineers, why would you invest in helping senior engineers grow? Building a culture of learning is the easiest way to recruit and retain good engineers at all levels.

Observing the ZPD in Software Engineers

If the zone of proximal development still feels abstract, let me give you a familiar example from my career. If you’ve successfully hired and trained another engineer before, this will likely sound familiar.

In 2019, I hired a new engineer at The Graide Network. She was straight out of a coding bootcamp, but very eager to learn new skills. I usually start new hires off with small technical debt projects because the stakes are low and they help them build confidence. Once our new hire had done a few linting and testing improvements, I assigned her some refactoring tasks.

A few weeks in, my new hire hit a couple of snags. I don’t remember the specifics, but she was working on a project in the middle of her zone of proximal development. We paired on the project for a couple of hours, and, pretty quickly, she was unstuck and making progress again.

The next time she ran up against a similar task, it was easy. She had taken some notes on our solution and had her previous code to reference. Solving that problem together armed her with the skills to solve similar issues independently in the future.

Applying the ZPD to Your Engineering Team

Because I’ve seen engineers get stuck and learn through pairing a number of times, I’ve made it a central part of my management process. Every company and manager will build a scaffold that works for them, but here are a few of the things I’ve learned when leveling up team members using the zone of proximal development:

1. Assess Each Engineer’s Current Skills

You can’t help your team members grow if you don’t know where they stand. I use an engineering skills rubric based on Medium’s Snowflake Tool, but there’s no “right” way to do this. Just make sure your assessment is objective and consistently applied across your team.

2. Create a Repeatable Structure

Engineers tend to like processes. Build a development process that facilitates pair programming, create official pathways for mentorship, and gather feedback from your team regularly. Build in time for pairing in your weekly work schedule. As you help each team member grow, you can decide how best to keep each of them in the ZPD as much as possible.

3. Assign Projects that Build on Prior Learning

Don’t force your engineers to hop around the codebase too much. If an engineer is just learning the frontend, start off by giving them some HTML and CSS tasks. As that becomes comfortable, give them some tweaks to existing JavaScript. Once they’ve done that a few times, ask them to build a new feature that’s similar to an existing one. Continue progressing the difficulty until the engineer has reached a level of competency that makes them productive and then move on to another skill set.

4. Give Effective Feedback

I’ve learned a lot about giving effective feedback in my time at The Graide Network. We use the seven hallmarks of effective feedback to ensure that team members get the most out of our coaching:

- Goal-oriented

- Prioritized

- Actionable

- Student Friendly

- Timely

- Consistent

- Ongoing

Get those right and you’ll be well on your way to helping your team grow.

5. Encourage Independent Learning

Insecure managers worry that if their engineers learn too much outside of their core job, they’ll want to leave. Good managers realize that each of their employees has a career that will span multiple companies. It’s a point of pride for Google and Apple that everyone wants to hire their former employees, and it should be for you as well.

I ask my employees to spend roughly four hours every week learning a new skill, and then we talk about what we learned at our weekly retrospective. This keeps us accountable and allows the whole team to benefit from each member’s learning.

6. Reassess Each Engineer Regularly

Finally, set up a time at least twice a year to assess the number and difficulty of tasks that each engineer can do independently. Junior engineers should be adding new skills rapidly. While senior engineers won’t tack on as many new skills per year, the weight and value of those skills should increase. If that’s not the case, figure out how to get your engineers into the zone of proximal development again.

Conclusion

The zone of proximal development is one of the many mental models available to engineering managers. I’ve found it helpful when creating training and onboarding programs, but it’s far from the only way to build a successful engineering organization. If you have thoughts, I’d love to hear them. Feel free to reach out on Twitter or in the comments below.

Karl Hughes

Karl Hughes is a software engineer, startup CTO, and writer. He's the founder of Draft.dev.