.NET 6 Has Arrived: Here Are a Few of My Favorite Things

Summarize with AI:

In this article, let’s explore .NET 6 features like Hot Reload, minimal APIs, HTTP Logging and Blazor improvements.

For the second straight November, .NET developers have received an early holiday gift: a new release of the .NET platform. Last month, Microsoft made .NET 6 generally available—and hosted a virtual conference to celebrate its new features.

What were the goals of .NET 6? If you look at themesof.net, you can quickly see the themes of the .NET 6 release, which include some of the following:

- Appeal to net-new devs, students and new technologists

- Improve startup and throughput using runtime exception information

- The client app development experience

- Recognized as a compelling framework for cloud-native apps

- Improve inner-loop performance for .NET developers

We could spend the next 10 blog posts writing about all the new .NET 6 improvements and features. I’d love to do that, but I haven’t even started shopping for the holidays.

Instead, I’d like to show off some of my favorite things that I’ll be using on my .NET 6 projects. Most of these changes revolve around web development in ASP.NET Core 6 since this site focuses on those topics.

Hot Reload

Way back in April, I wrote here about the Hot Reload capability in .NET 6. We’ve come a long way since then, but I felt the same as I do now: This is the biggest boost to a .NET web developer’s productivity over the last few years. If you aren’t familiar with Hot Reload, let’s quickly recap.

The idea of “hot reload” has been around for quite a few years: You save a file, and the change appears almost instantaneously. Once you work with hot reloading, it’s tough to go back.

As the .NET team tries to attract outsiders and new developers, not having this feature can be a non-starter to outsiders: It’s table stakes for many developers. The concept is quite popular in the frontend space, and .NET developers have been asking for this for a while. (Admittedly, introducing hot reload to a statically typed language is much more complex than doing it for a traditionally interpreted language like JavaScript.)

With .NET 6, you can use Hot Reload to make changes to your app without needing to restart or rebuild it. Hot Reload doesn’t just work with static content, either—it works with most C# use cases and also preserves the state of your application as well—but you’ll want to hit up the Microsoft Docs to learn about unsupported app scenarios.

Here’s a quick example to show how the application state gets preserved in a Blazor web app. If I’m in the middle of an interaction and I update the currentCount from 0 to 10, will things reset? No! Notice how I can continue increasing the counter, and then my counter starts at 10 when I refresh the page.

You can leverage Hot Reload in whatever way you prefer: Powerful IDEs like JetBrains Rider and Visual Studio 2022 have this capability. You can also utilize it from the command line if you prefer (yes, we do). It’s important to mention that this works for all ASP.NET Core Web apps.

Minimal APIs

Have you ever wanted to write simple APIs in ASP.NET Core quickly but felt helpless under the bloat of ASP.NET Core MVC, wishing you could have an Express-like model for writing APIs?

The ASP.NET team has rolled out minimal APIs—a new, simple way to build small microservices and HTTP APIs in ASP.NET Core. Minimal APIs hook into ASP.NET Core’s hosting and routing capabilities and allow you to build fully functioning APIs with just a few lines of code.

Minimal APIs do not replace building APIs with MVC—if you are building complex APIs or prefer MVC, you can keep using it as you always have—but it’s an excellent approach to writing no-frills APIs. We wrote about it in June, but things have evolved a lot since then. Let’s write a simple API to show it off.

First, the basics: Thanks to lambdas, top-level statements, and C# 10 global usings, this is all it takes to write a “Hello, Telerik!” API.

var app = WebApplication.Create(args);

app.MapGet("/", () => "Hello, Telerik!");

app.Run();

Of course, we’ll want to get past the basics. How can I really use it? Using WebApplication, you can add middleware just like you previously would in the Configure method in Startup.cs. In .NET 6, your configuration takes place in Program.cs instead of a separate Startup class.

var app = WebApplication.Create(args);

app.UseResponseCaching();

app.UseResponseCompression();

app.UseStaticFiles();

// ...

app.Run();

If you want to do anything substantial, though, you’ll want to add services using a WebApplicationBuilder (again, like you typically would previously in the ConfigureServices method in Startup.cs):

var builder = WebApplication.CreateBuilder(args);

builder.Services.AddSingleton<MyCoolService>();

builder.Services.AddSingleton<MyReallyCoolService>();

builder.Services.AddSwaggerGen(c =>

{

c.SwaggerDoc("v1", new() {

Title = builder.Environment.ApplicationName, Version = "v1" });

});

var app = builder.Build();

// ...

app.Run();

Putting it all together, let’s write a simple CRUD API that works with Entity Framework Core and a DbContext. We’ll work with some superheroes because, apparently, that’s what I do. With the help of record types, we can make our data models a little less verbose, too.

using Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore;

var builder = WebApplication.CreateBuilder(args);

builder.Services.AddDbContext<SuperheroDb>(o => o.UseInMemoryDatabase("Superheroes"));

builder.Services.AddSwaggerGen(c =>

{

c.SwaggerDoc("v1", new() {

Title = builder.Environment.ApplicationName, Version = "v1" });

});

var app = builder.Build();

app.MapGet("/superheroes", async (SuperheroDb db) =>

{

await db.Superheroes.ToListAsync();

});

app.MapGet("/superheroes/{id}", async (SuperheroDb db, int id) =>

{

await db.Superheroes.FindAsync(id) is Superhero superhero ?

Results.Ok(superhero) : Results.NotFound();

});

app.MapPost("/superheroes", async (SuperheroDb db, Superhero hero) =>

{

db.Superheroes.Add(hero);

await db.SaveChangesAsync();

return Results.Created($"/superheroes/{hero.Id}", hero);

});

app.MapPut("/superheroes/{id}",

async (SuperheroDb db, int id, Superhero heroInput) =>

{

var hero = await db.Superheroes.FindAsync(id);

if (hero is null)

return Results.NotFound();

db.Update(heroInput);

await db.SaveChangesAsync();

return Results.NoContent();

});

app.MapDelete("/superheroes/{id}",

async (SuperheroDb db, int id) =>

{

var hero = await db.Superheroes.FindAsync(id);

if (hero is null)

return Results.NotFound();

db.Superheroes.Remove(hero);

await db.SaveChangesAsync();

return Results.Ok();

});

app.Run();

record Superhero(int Id, string? Name, int maxSpeed);

class SuperheroDb : DbContext

{

public SuperheroDb(DbContextOptions<SuperheroDb> options)

: base(options) { }

public DbSet<Superhero> Superheroes => Set<Superhero>();

}

As you can see, you can do a lot with minimal APIs while keeping them relatively lightweight. If you want to continue using MVC, that’s your call—but with APIs in .NET, you no longer have to worry about the overhead of MVC if you don’t want it. If you want to learn more, David Fowler has put together a comprehensive document on how to leverage minimal APIs—it’s worth checking out.

Looking at the code sample above, it’s easy to wonder if this is all a race to see what we can throw in the Program.cs file and how easy it is to get messy. This can happen in any app—I don’t know about you, but I’ve seen my share of controllers that were rife for abuse.

It’s essential to see the true value of this model—not how cool and sexy it is to write an entire .NET CRUD API in one file, but the ability to write simple APIs with minimal dependencies and exceptional performance. If things look unwieldy, organize your project as you see fit, just like you always have.

Simplified HTTP Logging

How often have you used custom middleware, libraries or solutions to log simple HTTP requests? I’ve done it more than I’d like to admit. .NET 6 introduces HTTP Logging middleware for ASP.NET Core apps that log information about HTTP requests and responses for you, like:

- Request information

- Properties

- Headers

- Body data

- Response information

You can also select which logging properties to include, which can help with performance too.

To get started, add this in your project’s middleware:

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app, IWebHostEnvironment env)

{

app.UseHttpLogging();

// other stuff here, removed for brevity

}

To customize the logger, you can use AddHttpLogging:

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddHttpLogging(logging =>

{

logging.LoggingFields = HttpLoggingFields.All;

logging.RequestHeaders.Add("X-Request-Header");

logging.ResponseHeaders.Add("X-Response-Header");

logging.RequestBodyLogLimit = 4096;

logging.ResponseBodyLogLimit = 4096;

});

}

If we want to pair this with a minimal API, here’s how it would look:

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.HttpLogging;

var builder = WebApplication.CreateBuilder(args);

builder.Services.AddHttpLogging(logging =>

{

logging.LoggingFields = HttpLoggingFields.All;

logging.RequestHeaders.Add("X-Request-Header");

logging.RequestHeaders.Add("X-Response-Header");

logging.RequestBodyLogLimit = 4096;

logging.ResponseBodyLogLimit = 4096;

});

var app = builder.Build();

app.UseHttpLogging();

app.MapGet("/", () => "I just logged the HTTP request!");

app.Run();

Blazor Improvements

.NET 6 ships with many great updates to Blazor, the client-side UI library that’s packaged with ASP.NET Core. I want to discuss my favorite updates: error boundaries, dynamic components and preserving pre-rendered state.

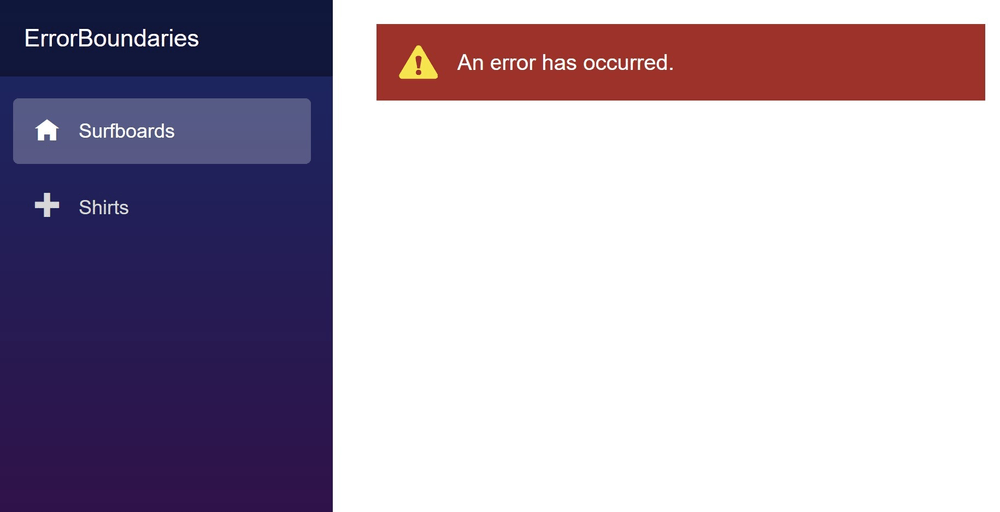

Error Boundaries

Blazor error boundaries provide an easy way to handle exceptions within your component hierarchy. When an unhandled exception occurs in Blazor Server, it’s treated as a fatal error because the circuit hangs in an undefined state. As a result, your app is as good as dead, it loses its state, and your users are met with an undesirable An unhandled error has occurred message, with a link to reload the page.

Inspired by error boundaries in React, the ErrorBoundary component attempts to catch recoverable errors that can’t permanently corrupt state—and like the React feature, it also renders a fallback UI.

I can add an ErrorBoundary around the @Body of a Blazor app’s default layout, like so.

<div class="main">

<div class="content px-4">

<ErrorBoundary>

@Body

</ErrorBoundary>

</div>

</div>

If I get an unhandled exception, I’ll get the default fallback error message.

Of course, you can always customize the UI yourself.

<ErrorBoundary>

<ChildContent>

@Body

</ChildContent>

<ErrorContent>

<p class="custom-error">Woah, what happened?</p>

</ErrorContent>

</ErrorBoundary>

If you’d like the complete treatment, check out my post from earlier this summer. It still holds up (even the MAUI Man references).

Dynamic Components

What happens if you want to render your components dynamically when you don’t know your types ahead of time? It previously was a pain in Blazor through a custom render tree or declaring a series of RenderFragment components. With .NET 6, you can render a component specified by type. When you bring in the component, you set the Type and optionally a dictionary of Parameters.

<DynamicComponent Type="@myType" Parameters="@myParameterDictionary" />

I find dynamic components especially valuable when working with form data—you can render data based on selected values without iterating through a bunch of possible types. If this interests you (or if you like rockets), check out the official documentation.

Preserving Pre-rendered State

Despite all the performance and trimming improvements with Blazor WebAssembly, initial load time remains a consideration. To help with this, you can prerender apps from the server to help with its perceived load time. This means that Blazor can immediately render your app’s HTML while it is wiring up its dynamic bits. That’s great, but it also previously meant that any state was lost.

Help has arrived. To persist state, there’s a new persist-component-state tag helper that you can utilize:

<component type="typeof(App)" render-mode="ServerPrerendered" />

<persist-component-state />

In your C# code, you can inject PersistComponentState and register an event to retrieve and ultimately persist the objects. On subsequent loads, your OnInitializedAsync method can retrieve data from the persisted state—if it doesn’t exist, it’ll get the data from your original method (typically a service of some sort).

To see it in action, check out the Microsoft documentation.

C# 10 Updates

Along with .NET 6, we’ve also got a new version of C#—C# 10. It ships with some great new features, like file-scoped namespaces, global usings, lambda improvements, extended property patterns, null argument checks and much more. Check out Joseph Guadagno’s blog post for more details, as well as Microsoft’s blog post.

Dave Brock

Dave Brock is a software engineer, writer, speaker, open-source contributor and former Microsoft MVP. With a focus on Microsoft technologies, Dave enjoys advocating for modern and sustainable cloud-based solutions.